My mom has an extremely tender heart. Despite battling schizophrenia for the majority of the past two decades, she still manages to express that tenderness, sometimes in the smallest—but most profound—of ways.

My happiest memories of my mom center around Christmas. It’s like her illness went into hiding during the month of December, and in its place emerged a walking heart with arms. Christmas was, and always will be, my mom. I can remember feeling like the luckiest kid on the planet when she’d bring up the boxes of decorations from the basement, each one labeled with her handwriting, the unique sometimes half-lowercase-half-uppercase style that has always felt like home to me.

She’d let me help her open each box and watch me squeal with delight at the memories packed inside. And I’d watch her open some of those boxes, carefully lifting out and unwrapping from white tissue paper the many treasures that had become a part of our family story. Snow globes, angel candle holders, plush snow dolls… Everything was wrapped in white tissue paper, and you could see just how much that tissue paper represented the tenderness of my mom’s heart, her desire to care for whatever small things she could when the big things—like me or my brother—were too much for her illness to handle.

That was the thing about my mom—and still is: tender. Despite the psychotic episodes, the delusions, obsessive-compulsive behaviors, or utter personality change, there were still moments of tenderness in between. And I cherished them. Wrapped myself up in them. Tucked them away within me. She was in there, not her illness.

Decorating the Christmas tree with the family—me, my mom, my dad, and my older brother, Geoff—was one of the moments of Christmas that felt so normal, safe, and free from the disease that had made a permanent home inside of my mother. And when we came to the boxes marked Ornaments, I always knew that the love my mother had for us, but couldn’t always show, would emerge from within them.

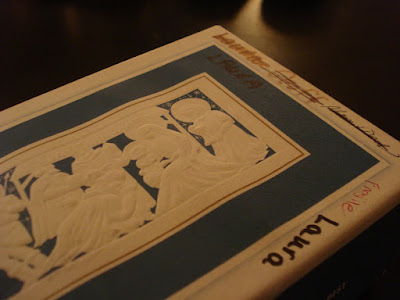

Within the larger, brown moving boxes we’d collected over the years were smaller boxes of all shapes and sizes: old stationary boxes, shoe boxes, gift boxes. And on each box my mother’s half-lowercase-half-uppercase handwriting appeared: LauRa, GEoff, Mom & DAd, GEoff, GeoFf, LAuRa. She had taken the time at the end of each Christmas, when it was time to dismantle the tree, to individually wrap each ornament in white tissue paper and place it in a box labeled for the person whose ornaments were inside. That way, during the next Christmas season, we’d each have our own boxes of treasures to unwrap from the white tissue paper that had become a part of our family history, and place those treasures upon our beloved tree.

Just last night, as I decorated my own tree here in my apartment, I unwrapped some of those boxes labeled with my mother’s handwriting. And for the first time, schizophrenia didn’t exist. She was right there. Just my mom. Her tender heart beating in my hands, beating in the shape of a small box with my name on it.

with love from Pittsburgh,

Laura

My happiest memories of my mom center around Christmas. It’s like her illness went into hiding during the month of December, and in its place emerged a walking heart with arms. Christmas was, and always will be, my mom. I can remember feeling like the luckiest kid on the planet when she’d bring up the boxes of decorations from the basement, each one labeled with her handwriting, the unique sometimes half-lowercase-half-uppercase style that has always felt like home to me.

She’d let me help her open each box and watch me squeal with delight at the memories packed inside. And I’d watch her open some of those boxes, carefully lifting out and unwrapping from white tissue paper the many treasures that had become a part of our family story. Snow globes, angel candle holders, plush snow dolls… Everything was wrapped in white tissue paper, and you could see just how much that tissue paper represented the tenderness of my mom’s heart, her desire to care for whatever small things she could when the big things—like me or my brother—were too much for her illness to handle.

That was the thing about my mom—and still is: tender. Despite the psychotic episodes, the delusions, obsessive-compulsive behaviors, or utter personality change, there were still moments of tenderness in between. And I cherished them. Wrapped myself up in them. Tucked them away within me. She was in there, not her illness.

Decorating the Christmas tree with the family—me, my mom, my dad, and my older brother, Geoff—was one of the moments of Christmas that felt so normal, safe, and free from the disease that had made a permanent home inside of my mother. And when we came to the boxes marked Ornaments, I always knew that the love my mother had for us, but couldn’t always show, would emerge from within them.

Within the larger, brown moving boxes we’d collected over the years were smaller boxes of all shapes and sizes: old stationary boxes, shoe boxes, gift boxes. And on each box my mother’s half-lowercase-half-uppercase handwriting appeared: LauRa, GEoff, Mom & DAd, GEoff, GeoFf, LAuRa. She had taken the time at the end of each Christmas, when it was time to dismantle the tree, to individually wrap each ornament in white tissue paper and place it in a box labeled for the person whose ornaments were inside. That way, during the next Christmas season, we’d each have our own boxes of treasures to unwrap from the white tissue paper that had become a part of our family history, and place those treasures upon our beloved tree.

Just last night, as I decorated my own tree here in my apartment, I unwrapped some of those boxes labeled with my mother’s handwriting. And for the first time, schizophrenia didn’t exist. She was right there. Just my mom. Her tender heart beating in my hands, beating in the shape of a small box with my name on it.

with love from Pittsburgh,

Laura

0 lovely bits o' feedback.:

Post a Comment